Edmund Clark in Conversation with Sophia Greiff

The question of representation, of visibility and absence of information, and how this affects our knowledge and understanding of current affairs and conflicts, is a recurring theme in Edmund Clark’s work. He examines the visual language of the global ‘war on terror’ and engages with censorship, unseen experiences, and hidden mechanisms of state control and incarceration. In his projects he exploits a wide range of interactions between images and texts – with images functioning as carriers of experience or as blank spaces, documents that appear as images or texts that trigger visual memories.

Sophia Greiff: Ed, when you spoke at our image/con/text symposium, you titled your lecture Bending the Screen: Ekphrasis, Plain Sight and the Monster within, which already hints at the various ways in which you approach image-text relationships. I would like to trace these different aspects and strategies, starting with the question: Why is it important for image-makers and audiences to bend their screens?

Edmund Clark: The title is partly a tribute and a reference to Fred Ritchin, who in his book Bending the Frame calls for image-makers to seek new or alternative ways to make work, in order to engage audiences and ideally effect change.1 Before bending their frames, image-makers must consider how the subjects they explore are represented and be aware of the messages that their potential audience will have encountered, the images and texts that are present in – or, indeed, absent from – their audiences’ minds.

You know, the time of everyone receiving the same information through a limited number of publications or broadcasters is obviously completely gone. We no longer have shared common sources of knowledge but a fragmented audience receiving a multiplicity of messages from different platforms. Our screens are targeting us with messages of advertising, propaganda, potential news … this is a kind of battlefield of imagery and text and quite often the messages are incredibly simplistic. They get repeated and repeated and inhibit people from engaging with a subject in a more complex and nuanced way. I think many of these messages are received in the same way we receive advertising. We’re not even conscious of how we’re reacting to them but they stimulate familiar patterns in our brains. If you can do something to create some form of dissonance, of surprise or discomfort, that could be the way to engage someone. So we need to reflect on what’s hiding behind the screen and try to introduce some of the complexity of alternative messages to our audiences.

SG: Could you elaborate how the operating modes of advertising relate to the way we receive information about current events?

EC: A lot of advertising is about trying to reassure people that they’ve bought the right thing and made the right decision. And I think with the fragmentation of news and platforms, a lot of people are not actually looking for new, different information but seeking messages that reconfirm that they believe the right thing, that they are identified with the right group. These are the same kind of tropes and simplistic forms of representation that I’m trying to question. The subjects I deal with are hugely weighted political and emotional subjects that are represented in incredibly simplistic ways. Terror and war tend to come with very simplistic messages.

SG: How did your interest in issues of representation and your focus on these unseen processes develop?

EC: I’ve been through three stages of learning about and analysing human behaviour.

First, I did a history degree, which is all about looking at patterns and trying to understand what happened and why people behaved in certain ways. But it’s also about taking evidence and information, about interpretation and argument and putting across a perspective. I then worked in research for marketing and advertising. When you’re starting an advertising campaign or developing a new product, you are literally showing stimuli to potential purchasers and seeing how they react; whether they respond positively to this image or that message. It’s about emotion and about creating the right triggers to influence the consumer’s behaviour. Then I went back to art college and studied photojournalism, where I was dealing with journalistic research and ideas about truth and objectivity, about being a reliable source. That was very different to the five years I spent looking at how people actually did respond to images and text.

SG: You then chose to work in the field of art instead of photojournalism …?

EC: I’m making work that responds to a media perspective and questions the way in which the media sees the world. Photojournalism can be incredibly powerful. But it is very closely aligned with conventional media forms, which don’t really work anymore. The traditional model of the photojournalist going out into the world, taking photographs that are reproduced in magazines, usually with someone else’s text and this is how you understand the world – this model has been superseded. Those are still quite familiar ways of seeing and being shown subjects. But it’s a sort of service enterprise, where you’re commissioned to make work that feeds into those forms of communication. Whereas art has always been more anarchic. It’s obviously also connected to the marketplace and tied in with big institutions. But at the same time it just allows more freedom. And with this multiplicity of platforms, we need more creative approaches to try and deconstruct what’s happening. So when I talk about bending the screen, that involves looking for forms that don’t fit into those familiar patterns.

SG: Do you think that today’s image-makers need more creativity and persuasiveness to reach people and motivate critical engagement?

EC: I think you have to be more aware of the appropriateness, the conceptual validity of what you are doing. Photography is an acquisitive act: you create a piece of visual knowledge by putting something in a frame, making a choice and saying this is important. But can I speak for a subject? It might not be appropriate for me to make work about them. Or I have to make that incredible leap, where the inappropriateness of me looking at something is fundamentally part of the work. What I did with The Mountains of Majeed was completely inappropriate, for example: taking pictures made by an Afghan artist, using them without his permission, just total Western curation.2 But that was part of the point I wanted to make. It’s a reflection of the process of occupation and resistance in a place like Afghanistan, a reflection of the West’s treatment of Afghanistan.

SG: I think your project Guantanamo: If the Light Goes Out (2010) is a good example of what you said about disrupting simplistic representations. You were searching for alternative images of a place that is strongly associated with certain imagery and messages. How did you proceed?

EC: I started by responding to the fact that British men who had been held in Guantanamo Bay and were thought of as the worst of the worst, discussed in the same breath as those who planned 9/11, came back to the United Kingdom. They never had a proper legal process in Guantanamo and then they were back living in Great Britain, completely innocent, just like you and me. Yet, they would forever be associated with Guantanamo. I talked to the lawyer who had represented them and they didn’t want to have anything to do with media or publicity. But eventually I was able to take photographs inside their homes, and decided to focus on domesticity and the familiar rather than the exotic and demonised. It’s a work about that weird disconnect between the huge spectacle on our screens post-9/11, including, at that time, the problematic images of South Asian or Arab men with beards, the Osama bin Laden and terrorist trope, imbued with fear and terror – and the very ordinary, very British living spaces of people who had been released from Guantanamo Bay. I would love to say that this was a conscious visual strategy I devised at the time but actually it’s what I was living with, which was seeing this representation of extraordinary conflicts and then meeting people involved with them and experiencing something very different.

Edmund Clark, from the book Guantanamo. If the Light Goes Out, Dewi Lewis Publishing, 2010.

SG: In the eponymous book you also added two other kinds of space – the Guantanamo naval base, which houses the American community, and the camp complex where the detainees were held – and mixed them all up.3 You’re creating a connection between content and form that brings your own experience across and I think that’s something very specific about your approach …

EC: Yes, I mean my projects often take quite a long time – they are the product of processes of reflection which after a while start to reveal how something is going to work visually. When I started, I had no idea that I would go to Guantanamo Bay, and when I was there, I didn’t know what photographs I would come back with. But I had spent so much time researching the subject and realised that I had to try and represent something that we weren’t seeing, weren’t being told about this process. So I’m using three notions of personal and domestic space to create a photographic narrative, which is unexpected and confusing. I don’t tell you what you’re looking at; you don’t necessarily know initially whether it’s home, base or a detention space. I’m using the idea of dissonance to represent something else about Guantanamo Bay: the process of interrogation that takes place there, which is predicated on making people disorientated, making them dependent on their interrogator, making them paranoid. I’m using a virtually wordless narrative to create this sense of confusion in the minds of an audience.

SG: Sometimes you also correct your conceptual decisions. You initially showed the Guantanamo images as a slide show with music, but later refrained from doing so. Can you explain why?

EC: I felt it was inappropriate. The music was from the torture playlist, so it was about that interrogation process and totally valid. But there was too much artifice going on. The way it was cut and sequenced it just felt a bit overdramatic, overworked, too authored. It doesn’t need that.

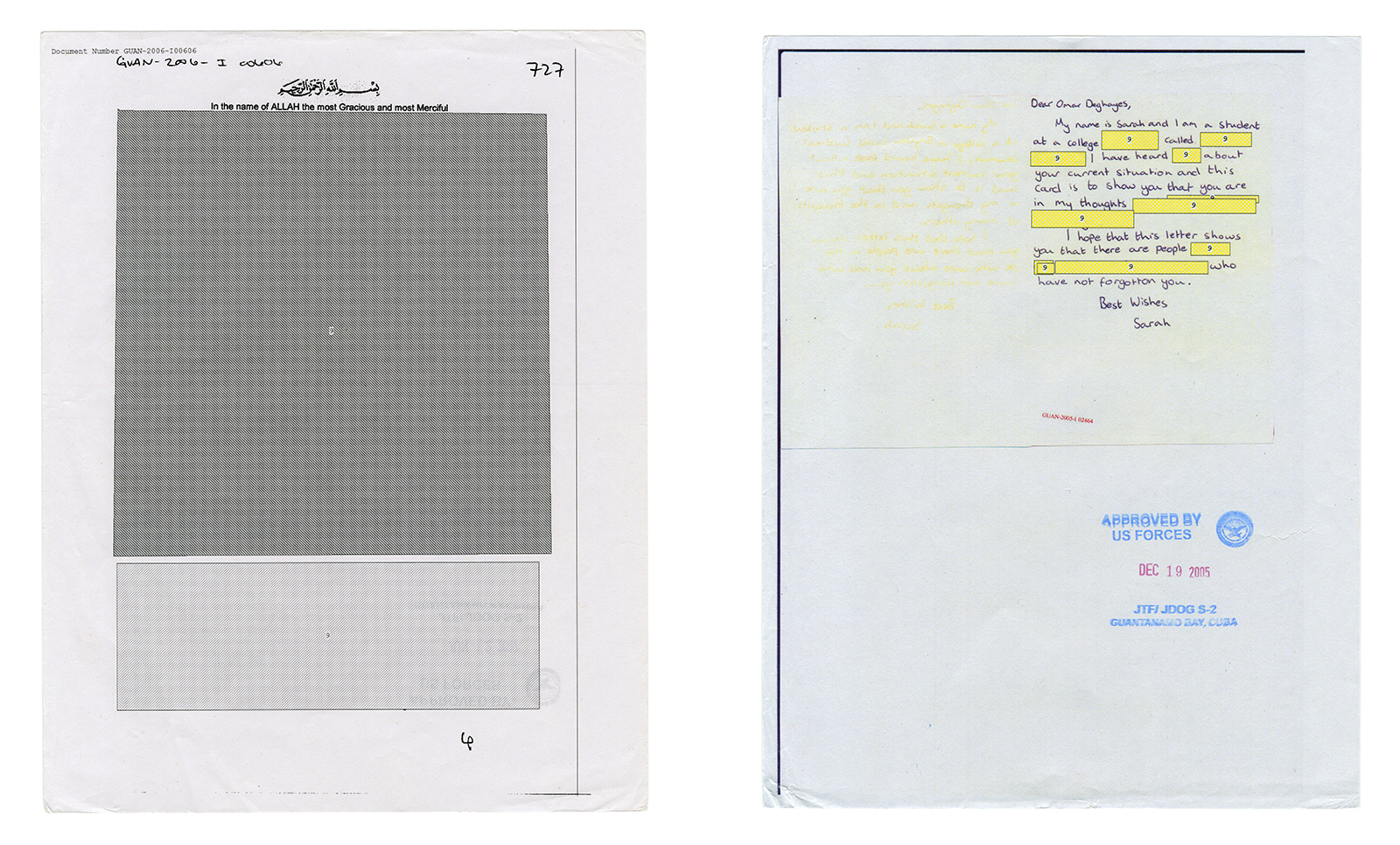

Edmund Clark, from the work Letters to Omar, 2010.

SG: In another work about Guantanamo titled Letters to Omar (2010), you decided not to take your own photographs at all and instead reproduced a prisoner’s personal letters. Do the documents say something about the context in which they were created, something that photographs documenting the situation couldn’t? Do they speak for themselves?

EC: Yes, they do. They represent one man’s experience during his six years of detention at Guantanamo Bay. He was at the highest level of non-compliance, which meant every detail of his life was controlled by his interrogator, including when and if he got mail and in what form. Everything he received went through a process of being scanned, redacted, stamped and given a unique Guantanamo archive number. At the end he got the scans, the relics of the original messages and cards. These are new images created by a bureaucratic process at Guantanamo Bay. I haven’t made them – a series of low-level military functionaries have made those images. Some were careless, back to front, upside down, a lot were black and white. They have been transformed through a process of degradation from a beautiful colour postcard to a scrappy piece of scanned paper with a low-resolution pixelated image. That’s a form of abuse, which speaks about an experience that I, as a photographer going to Guantanamo Bay and photographing these clean spaces, can’t show. Yes, they speak for themselves – they speak credibly eloquently, after taking them from one context and putting them in another. They are witnesses of the exercise of control by a state power, by an authority over that individual.

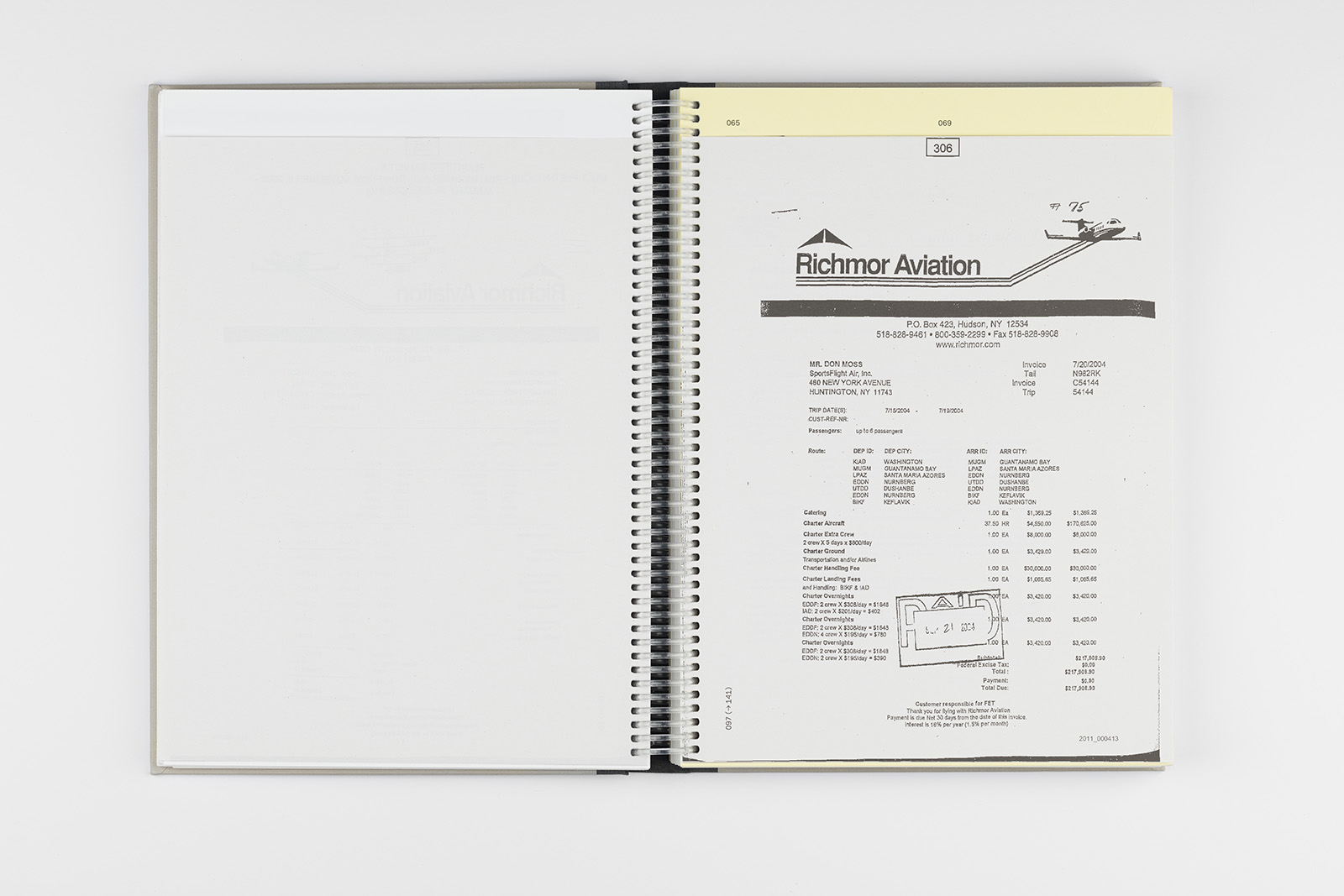

SG: Documents also play an essential and dominant role in Negative Publicity: Artefacts of Extraordinary Rendition (2011–2016).4 What do we learn from them in this case?

EC: This is a body of work that I made with a counter-terrorism investigator, Crofton Black, about the transportation of people between secret CIA sites around the world. The documents show these activities via the weak points of business accountability: invoices, documents of incorporation, and billing reconciliations produced by the small-town American businesses involved. Through them we can learn about the bureaucratic process of extraordinary rendition and about who was responsible for flying prisoners. We learn about the fragmented nature of this partially known and sometimes deliberately hidden subject, which happens in such ordinary places that we don’t even notice that it’s going on. We learn how the subject is obfuscated or covered up, so the documents expose falsehoods and misinformation. It’s also about Crofton Black’s research process, how he put together the paper trail that started to reveal this global network. Other forms of documentation that we chose to use show how the subject has been researched and represented by other organisations, like the European Union, the New York Law School or the Italian police.

Crofton Black, Edmund Clark, from the book Negative Publicity: Artefacts of Extraordinary Rendition, Aperture Foundation, 2015.

SG: The documents also hint at what we don’t get to see. They promise ‘plain sight’ but most of them have been censored, redacted and altered. Don’t they hide more than they are actually able to reveal?

EC: This is about the unseen. We are dealing with the visualisation of what we don’t know, we’re dealing with state secrecy. And that’s actually a very powerful trigger for an audience. What we don’t know is more interesting than what we do know. So these black rectangles and strikeouts are actually ways of engaging audiences, of making people question what is going on and reflect on what our governments are doing on our behalf. I mean, if they are happy to keep mock executions and waterboarding techniques on that list

of contents, what’s under the black rectangle? What does that say?!

SG: In his afterword Eyal Weizman refers to this as “negative evidence”, in the sense that “the very act of redaction is evidence in itself”: it shows that “something controversial, perhaps illegal, is within”.5 What I find almost as shocking, on the other hand, is that the documents also disclose the banality of this whole system.

EC: Absolutely. For example, there is an incredibly ordinary e-mail exchange between a company that rents airplanes and one of the logistics companies that was under contract with the American government:6 “I’m sorry, the client cancelled the flight for the 5th and the 28th. I will await further from them and let you know.” – “Just curious … do you think it has anything to do with all the media attention?” – “Absolutely not. Just an itinerary change for the passengers. :-).” This is one of my favourite banal everyday documents because it reveals that this process was not run by spies or the CIA – it was outsourced to logistics companies in Washington, who outsourced it to upstate New York airfields, to people working from home in Long Island. They were responsible for the organisation of the American government’s extrajudicial detention and transportation of individuals to be tortured in secret sites. Your next-door neighbour, working from home, organising flight schedules for companies around the world, one afternoon, really bored, typing away, smiley face. That smiley face is about complicity: “I know that the cargo on that plane is someone who’s going to be tortured. And I don’t care.” That smiley face is about an ethical choice someone has made. It’s hugely significant.

SG: You also responded photographically to this subject but in a way these images reveal as little as the redacted and unreadable documents, some photographs also being censored. Is there any information in the images?

EC: I didn’t want to make images about this subject in the beginning. There was nothing to see. You don’t get to see torture. You can’t verify anything. It’s in vain. The camera as a documentary tool: redundant. But the point of not being able to see anything, the sort of pointlessness of the photographic image as a vehicle for information was, in the end, very relevant. These images became a sort of extension or counterpoint of the black rectangle, of the façade – because they show the limits of what we know. They are sights and scenes that are incredibly ordinary, very easy to walk past, but when you stop and look at them they say something very troubling. Eyal Weizman wrote that we don’t get to see torture or detention in the book but we see the attempt to mask these procedures, the materiality and architecture of the secret. So again it’s about what’s behind the messages we receive on our screens. It’s about a system which was saying: “We’re doing all this to protect our values; we are about freedom, justice, democracy and fairness”, but was actually involved in highly illegal extrajudicial detention and torture. It’s about that hypocrisy, that crude dichotomy that people have to be aware of and understand.

SG: By transferring all these artefacts of research into the context of the photobook, you’re harnessing the authentic and objective aura of the official documents. But you also make your subjective influence and narrative as an author more tangible. In what sense is this story also fictionalised? How do we know that we can trust you?

EC: You don’t. I guess it could all be made up – the documents, … that hotel bedroom could be in West London instead of Skopje, it could have nothing to do with Khaled el-Masri.7 But on another level that’s also the whole point of the book. It’s about knowing and not knowing. You can’t trust me, no. But you can’t trust any artist. Do you trust the photojournalist? This goes back to making work that’s feeding the news media and is a part of that construct, where we’re told: “This is the truth, this is objective and believable.” Well, I don’t believe a lot of what I’ve heard about the war on terror. I don’t believe it when my government says: “We didn’t know what was happening to people when we helped organise their renditions to Libya, to Colonel Gaddafi.” I don’t believe it when the party I voted for says: “We knew nothing about it.”

I don’t believe them. So who do you believe?!

SG: This question of belief and trust makes me think of the photo festival in Arles, where a new category of photobook award was introduced in 2016: the Photo Text Book Award. Negative Publicity won the first prize, so your approach also seems to represent a current trend on the photobook market: publications that include archival material, found footage and a considerable amount of text, and are often referred to as ‘research-based books’. Do you have an idea where this tendency is coming from? Are images alone no longer trustworthy?

EC: Images alone can be fine – it just depends on the context. I think it’s partly a response to the multiplicity of images around us. So people use images which have already been made and curate work from other sources, or they collaborate with others. It’s a reflection of the greater complexity of the world we live in and comes back to questioning this incredibly privileged Western technological supremacy of photography. There’s a sort of mistrust in the individually authored point of view. So this also leads to a process of scrutinising the traditional photographic book form, the beautifully designed volume with a set of plates. Does it really have a point? Again this is about the importance of the conceptual validity of what we are looking at and who’s looking at it. But photographers and artists have always used the interactions of image and text.

SG: You mentioned that you also collaborated closely with the investigative journalist Crofton Black on Negative Publicity. Can you describe your cooperation and how it started?

EC: I met Crofton when I was working on the Guantanamo body of work. He was researching the rendition process, so I talked to him about developing something together but he was quite reserved. Eventually he agreed and we started with him sending me three or four files with thousands of documents that were important as evidence. I went through a lot of it quite quickly and selected what I felt was interesting and had impact visually. It was an ongoing conversation which also involved our designer Ben Weaver, who came into the project conception early on. Ben played quite an important part in terms of how the design related to the sequence. Crofton came up with the cross-referencing in the book. And the research information is nearly all his work, although there’s also other material that came out of my own journeys, sources and research processes.

SG: Why do you think Crofton eventually agreed to join forces?

EC: So far his research has had a traditional forensic purpose – he’s spoken at the Court of Human Rights in The Hague, he’s been involved in cases against the Polish and Lithuanian governments, so his work has had an effect in that context. Quite a lot of his work is on a website called The Rendition Project.8 But I think he was intellectually interested in doing something that gave him more of a creative outlet. Also recontextualising the information would reach audiences beyond the human rights and legal contexts, beyond courts of law, commissions or academics researching the topic. It says something else about the subject and it reaches a different audience.

SG: In your joint book you offer your readers various options for appropriating the story – page by page or browsing back and forth using the complex reference and index system. In your lecture you mentioned that this book is what Fred Ritchin calls a “hypertext”: “an explicit collaboration with the reader whose choice of pathways elicits differing narratives, an incarnation of Roland Barthes’ ‘active reader’”.9 Could you explain why you chose this strategy?

EC: There’s no point us sitting there, writing a book which says: “This terrible thing happened, these were human rights abuses, we should be dreadfully disappointed in our government.” It’s far more profound if people uncover that themselves. So we don’t initially tell you anything about the text, about the images. You have reference numbers which take you to other pages, into a process where you start to make connections between destinations, locations, court cases, messages. It’s about trying to create something that involves the audience going through a similar process of flashes of revelation and having to move around a space in order to reconnect the network. I remember a conversation with Susan Meiselas, who said: “Shouldn’t you talk about what’s happened to the individuals, shouldn’t their cases be there?” And I replied: “That’s not how we want the book to work.” Because if I give you a case study, let’s say of Khaled el-Masri or Abu Zubaydah10, you’ll learn something but you won’t actually experience anything about it, you won’t really understand the implications. But if you let their voices emerge through other sources, if you let the reader cross-reference and stumble upon a fragment of redacted document about how they were treated or you see the hotel bedroom where Khaled el-Masri was held for 23 days, that speaks volumes. That’s a very different experience. And it becomes less about them and the crimes they might be associated with, rightly or wrongly, and more about what was happening in the background and who’s responsible for it.

SG: However this demands a lot of activity and willingness from the reader. It can be quite overwhelming …

EC: It is overwhelming. I’ve not been able to read the whole book.

SG: So personalising and emotionalising a story could be a low-threshold strategy for engaging people and making them identify with others?

EC: It can be. It may work for a certain audience. But it often doesn’t work for me. You know, this book is not for the mainstream. It’s not going to make the ten o’clock news or be on the school curriculum. My work is quite difficult and involves a level of complexity and difference that affects the number of people I do get to reach. The more complicated you make something, the more nuanced, the smaller the audience becomes.

Installation view of the group show [Control] No Control at Hamburger Kunsthalle, 9 June to 23 September 2018.

EC: I think naturally it is very difficult to transfer a work into a gallery space. I’ve exhibited Negative Publicity in different ways.11 The first version in Mannheim was the simplest, with framed photographs and documents. The London version was basically a film and all the pages from the book on the wall – but probably no one ever stopped to go through all of them. In New York we tried to create networks and translate the experience of the investigative process into a gallery space. But I think that was perhaps too complicated. In Hamburg we developed something unique. We made this about the act of redaction and used just redacted images and texts. There is no contextualisation from us. Reading what’s left on the documents and viewing the act of redaction by the state authorities is all you need. You get enough information to know it’s about torture, secrecy, denial. You get enough to question what’s happening. I think that’s probably the most successful exhibited form of Negative Publicity. I also think it works aesthetically.

SG: But doesn’t this reduce the subject to an aesthetic experience instead of fostering critical engagement and interaction like the book does?

EC: I think different forms work in different contexts. If you make work for a museum or gallery or publish a limited edition book, that’s going to be a different kind of audience than on a mainstream website. My experience is that the more complicated forms we did in gallery spaces required people to give a lot of their time. So an exhibition might be a more engaging aesthetic experience, while in a book you can bring more information across.

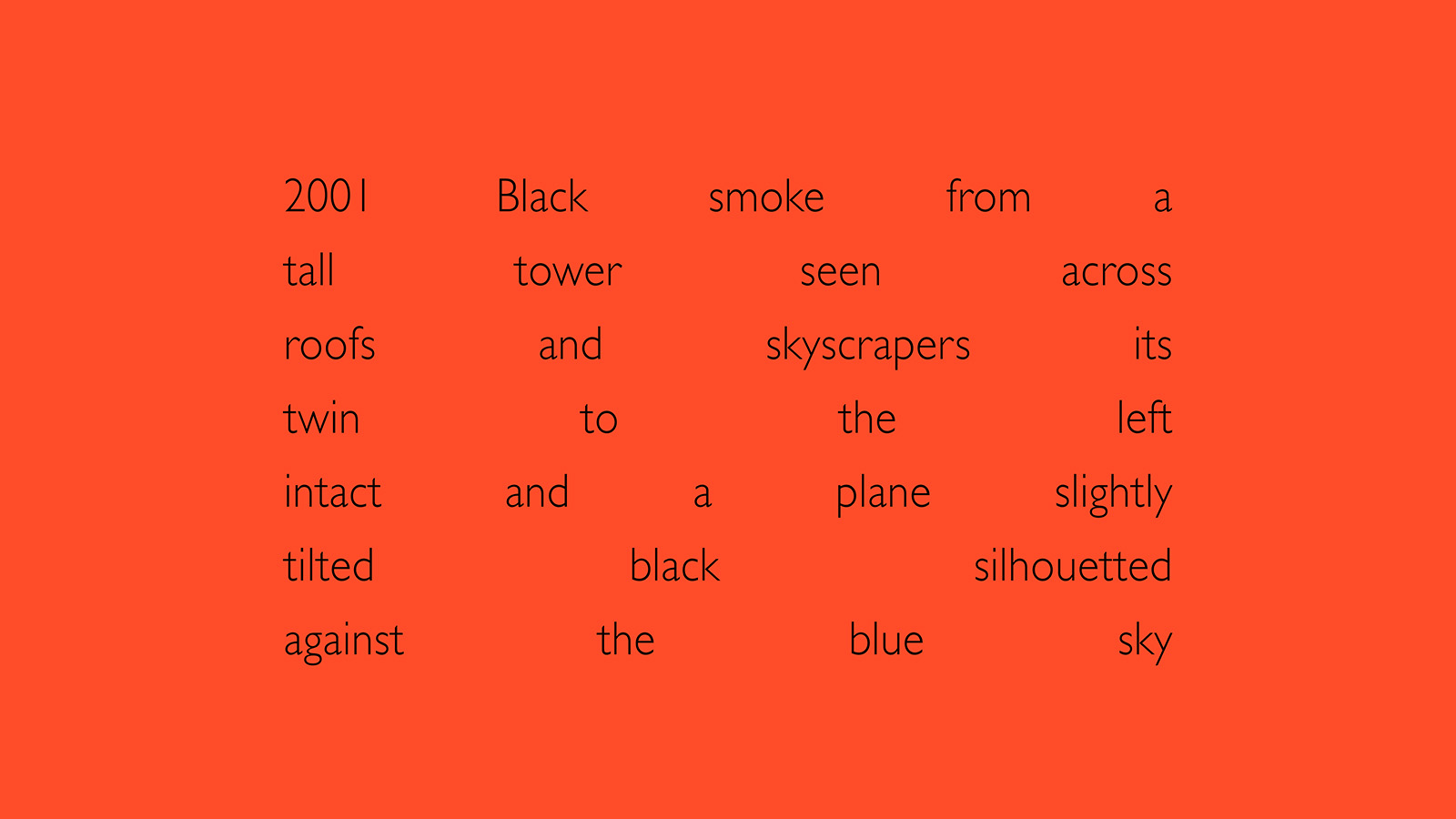

Edmund Clark, Max Houghton, still from the video Orange Screen, 2016.

SG: Let’s move from ‘plain sight’ to ‘ekphrasis’. In your video Orange Screen (2016) you use another strategy to question the mainstream form of representation in relation to the global war on terror. What was your approach in this work?

EC: The work was originally made for an exhibition at the Imperial War Museum in London, where I was asked to create a narrative about contemporary conflict. First there was this idea of a wall with news images that would recreate the media vision of the war on terror – but that was exactly what I didn’t want to do. Then Max Houghton came up with the idea to just use words and describe what I actually saw in those iconic images. This is called an ekphrasis, a textual description of a visual piece of art. And that was a revelation to me because then you really think about what’s in the picture. I want people to revisit, reimagine and reconnect with these images. I want them to explore whether they recall the image or the event itself. Most of us don’t remember 9/11 through being in New York; we remember it through fragments of images we saw. Most of us didn’t experience the war in Afghanistan but we have memories of Bin Laden videos and news footage of troops on patrol. These are visual representations, but all the implicit tropes and messages and reconfirmations of our beliefs are embedded in the images that we remember. The images become the carriers of our experience.

SG: Earlier you also spoke about the images of men with beards, which after 9/11 were generally equated with fear and terror. This construction of ‘the other’ as a monster is equally common when it comes to the visualisation of incarceration and criminality. For nearly five years you were artist-in-residence at HMP Grendon in the United Kingdom, which is Europe’s only wholly therapeutic prison. What where your experiences concerning representation when you were working there?

EC: One of the first things I was told was that I couldn’t make any work that revealed the identity of the prisoners, who are some of the most serious criminals in the country. But I realised that I had to confront this head-on because this is about how prisoners are seen and how they are represented in the media. If you’ve committed such crimes, if you are sent to prison, you literally disappear. You cease to be seen as a human being. In the kind of reductive binary discourse around this kind of criminality that has become typical in Britain, you have become a monster.

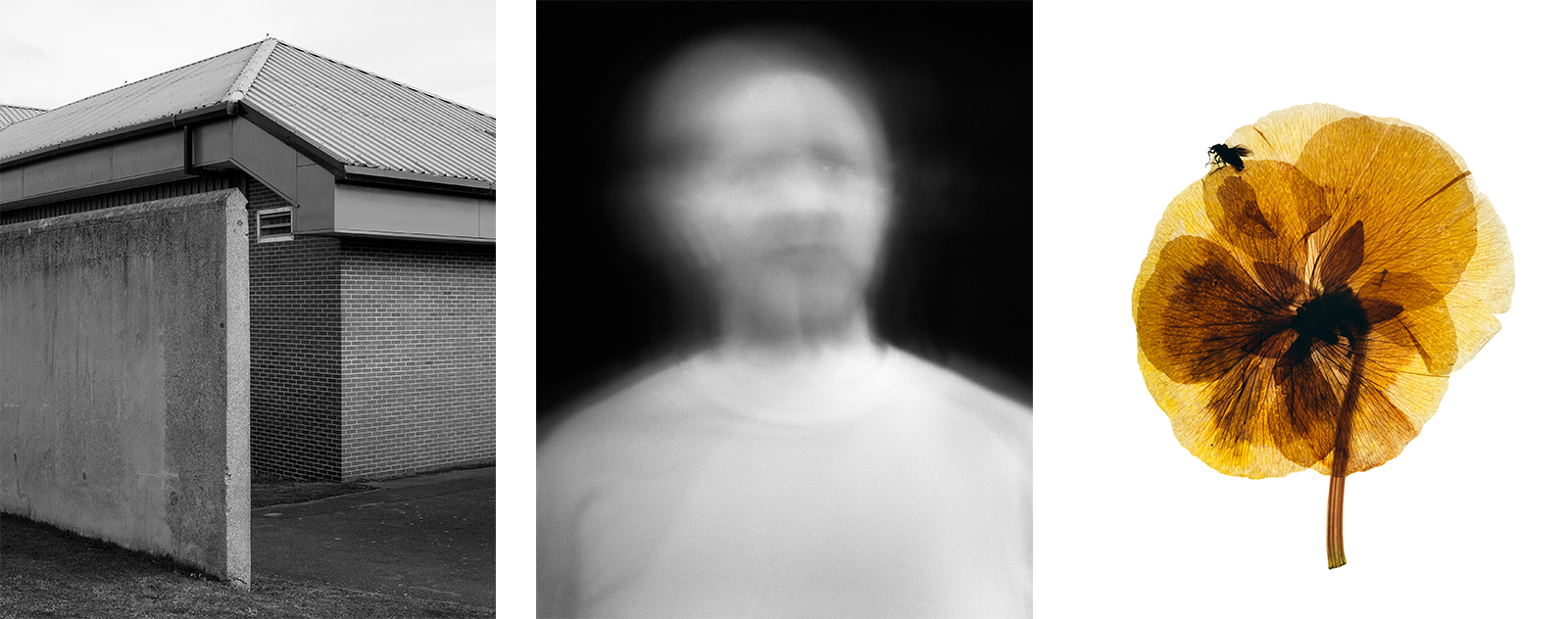

Edmund Clark, from the book My Shadow’s Reflection, Ikon Gallery/Here Press, 2017.

SG: You decided to use a pinhole camera for the portraits in My Shadow’s Reflection (2017). Can you explain why?

EC: I was interested in using it for conceptual reasons, because it’s related to notions of the panopticon and the idea of the cell, the dark chamber. But also there’s no lens. I didn’t create images of these men. We set the camera up in a group context and they took turns standing in front of it, talking about why they are there, what they had done, what’s been done to them. So these are images that the men made of themselves going through this process in this context. These are impressions of a conversation. This also plays with the ideas of Bertillon and his mug shots of prisoners, with this visual trope of the other. I didn’t want to perpetuate that kind of representation and at first I was very troubled by the images we made. So I took them back into the wing community meetings – and it was the responses that gave these images a purpose. It was as though creating these visual representations of themselves became an extension or a visual manifestation of the therapeutic processes they were going through in the prison. They became visual stimuli for the men to talk about how they saw themselves and how they felt people on the outside would see them.

SG: Would you say it was an artistic collaboration with the prisoners?

EC: No, this could never be an equal relationship. It was a participatory process. I wanted this work to be shaped by the creative therapies, by the experience of being in that environment. So I was not creating work myself, I was working in a context where these processes were generating the work.

SG: In the book you also included black and white architectural images of the prison and close-ups of delicate, colourful flowers.12 What role do the latter play?

EC: I picked, pressed and photographed plants and flowers which grew in this environment. Some of this flora was planted deliberately but a lot of it just grew haphazardly, randomly, chaotically. So my intention was to look at this variety and diversity. It’s about what we see as being beautiful or ugly, as accepted or rejected. When you put the flowers on a light box, when you get close up and look at this material in detail, you see every vein, every tear, every bit of rot. You see the fragility in these things. And it’s deliberately problematic to combine portraits of people who are killers and rapists with beautiful flowers. But that’s the whole point. Because I’m asking you to make and interpret these connections and decide whether they are appropriate.

SG: What’s next? What upcoming projects can we look forward to?

EC: I started a work about Brexit in Britain. And Crofton and I have been talking for a long time about a substantial new

project, which is about power, knowledge and the military industrial complex. Other than that, I’m interested in this ongoing process in Britain of stripping people of their British citizenship, people who have dual citizenship and have been caught up in the ongoing conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, Syria. There’s one example of a teenage woman who went out to Syria. Her grandparents originally came from Bangladesh, so we’ve stripped her of her British citizenship and said: “Well, she’s still got Bangladeshi citizenship, she could go there.” I find that legally and politically very troubling. We’re not allowed to make people stateless. It’s hugely irresponsible and it’s effectively denying that their lives in Britain played any part in why they became radicalised.

This conversation took place via Skype, 19 December 2019.

| 1 | Fred Ritchin, Bending the Frame. Photojournalism, Documentary, and the Citizen, New York 2013. See also Fred Ritchin’s contribution in this volume. |

| 2 | “The Mountains of Majeed is a reflection on the end of the war in Afghanistan through photography, found imagery and Taliban poetry. It looks at the experience of the vast majority of military personnel and civilian contractors who have serviced ‘OperationEnduring Freedom’ without ever engaging the enemy.Their vision of Afghanistan is what they see over the perimeters, or represented inside the walls, of enclaves like Bagram Airbase, the biggest base of ‘Operation Enduring Freedom’ and home for 40,000 personnel. Inside a dining facility at Bagram I found a series of simple paintings of mountains and monuments showing a different Afghanistan, by an Afghan artist called Majeed. These transcend the confines of the base taking the viewer to idealised passes and lakes in the Hindu Kush and other ranges.” Edmund Clark, The Mountains of Majeed, https://www.edmundclark.com/works/mountains-majeed/#text (last accessed 11 January2020). |

| 3 | Edmund Clark, Guantanamo. If the Light Goes Out, Stockport 2010. |

| 4 | See Crofton Black and Edmund Clark, Negative Publicity: Artefacts of Extraordinary Rendition, in this volume. |

| 5 | Eyal Weizman, “Strikeout: The Material Infrastructure of the Secret”, in: Crofton Black and Edmund Clark, Negative Publicity. Artefacts of Extraordinary Rendition, New York 2015, p.287. |

| 6 | See Black/Clark, Negative Publicity: Artefacts of Extraordinary Rendition, in this volume. |

| 7 | Khaled el-Masri “is a German and Lebanese citizen who was mistakenly abducted by the Macedonian policein 2003, and handed over to the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). While in CIA custody, he was flown to Afghanistan, where he was held at a black site and routinely interrogated, beaten, strip-searched, sodomized, and subjected to other cruel forms of inhumane and degrading treatment and torture. After El-Masri held hunger strikes, and was detained for four months in the ‘Salt Pit’, the CIA finally admitted his arrest and torture were a mistake and released him. He is believed to be among an estimated 3,000 detainees whom the CIA abducted from 2001–2005.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khalid_El-Masri (last accessed 11 January 2020); see also Black/Clark, Negative Publicity: Artefacts of Extraordinary Rendition, 2015, pp. 153, 281 et al. |

| 8 | University of Kent, The Rendition Project, www.therenditionproject.org.uk (last accessed 11January 2020). |

| 9 | See Fred Ritchin’s contribution in this volume. |

| 10 | “Abu Zubaydah is a Saudi Arabian citizen currently held by the S. in the Guantanamo Bay detention camp in Cuba. […] Zubaydah was captured in Pakistan in March 2002 and has been in United States custody ever since, including four-and-a-half years in the secret prison network of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). He was transferred among prisons in various countries including a year in Poland, as part of a United States’ extraordinary rendition program. During his time in CIA custody, Zubaydah was extensively interrogated; he was waterboarded 83 times and subjected to numerous other torture techniques including forced nudity, sleep deprivation, confinement in small dark boxes, deprivation of solid food, stress positions, and physical assaults. Videotapes of some of Zubaydah’s interrogations are amongst those destroyed by the CIA in 2005.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abu_Zubaydah (last accessed 11 January 2020); see also Black/Clark, Negative Publicity: Artefacts of Extraordinary Rendition, 2015, pp. 159, 190, 281 et al. |

| 11 | Mannheim: solo show Terror Incognitus at Zephyr, Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen, 31 January to 29 May 2016, curated by Thomas Schirmböck. London: solo show War of Terror at Imperial War Museum, 28 July 2016 to 28 August 2017, curated by Hilary Roberts and Kathleen Palmer. New York: solo show The Day the Music Died at the International Center of Photography, 26 January to 6 May 2018, curated by Erin Barnett. Hamburg: group show [Control] No Control at Hamburger Kunsthalle, part of Triennial of Photography, 9 June to 23 September 2018, curated by Petra Roettig and Stephanie Bunk. |

| 12 | Edmund Clark, My Shadow’s Reflection, Birmingham/London 2017. |

English

English