Laia Abril in Conversation with Sophia Greiff

The combination and interplay of images and text in the format of the photobook is by no means an entirely new phenomenon. A distinct subgenre has, however, been emerging in recent years. It is characterised by the integration of archive material, found footage and reciprocally corroborating documents – and by the deliberate exhibition of the intensive research process on which the respective work is based. Frequently examining complex and hidden subjects, these so-called ‘research-based photobooks’ employ the authority of documents and navigate between the educational impetus of photojournalism and the experimental nature of artistic practice. The Epilogue and On Abortion by the photographer and artist Laia Abril are two such photobooks that have received great critical acclaim. Investigating topics that are intimate and uncomfortable, sometimes illegalised, relating to taboos and stigma, she divides her long-term projects into chapters1, using photography, text, archival materials, video and sound to create different experiences for diverse platforms and audiences.

Sophia Greiff: Laia, in all of your projects you are making hidden stories visible and putting complex ethical and moral issues up for discussion. How did this direction develop and what interests you about it?

Laia Abril: I always had the feeling that the things that were important to me, that touched me, were not shown on the news and in classical journalism. It was this lack of representation that first made me want to go to uncomfortable places and this interest grew from project to project. It’s challenging – and in a way my approach is completely against photography: I’m trying to visualise what you can’t see. There are so many things that would be so much easier to photograph, things that don’t elude visibility. But that’s part of my relationship with the medium: wondering what we get to see and are able to react to. What do we not get to see, what do we prefer not to look at? The things that we don’t want to see – or are not supposed to – are the ones that remain invisible in society. And they also remain invisible to the medium. I find it fascinating what an impact it can have on people when you visualise things that matter to them. How people are touched when something painful or something they maybe don’t understand about their journey or their life is on the table. It’s almost like a healing process, a cathartic process – for other people but also for me.

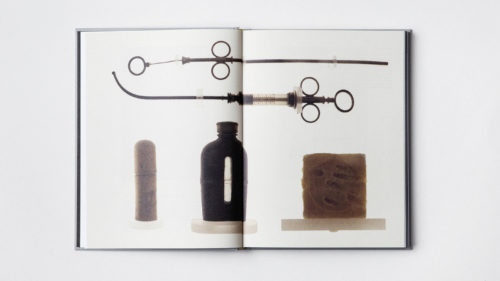

SG: All your previous projects are based on extensive, careful and mostly long-term research. For On Abortion you talked to numerous experts, scientists and affected persons worldwide; you collected documents and data, objects and stories. Why did you decide to make these research materials visible?

LA: I think it’s very closely connected to the idea that we need to face things. I like this expression in English, ‘to face’: we have to look at things. Because we can think about certain matters, we can imagine them – but sometimes our perspective only changes when we actually see them. They become real in our minds. For example, when I started researching my first long-term project On Eating Disorders around ten years ago, the pro-anorexic community was not as visible as it is these days with Instagram and social networks. Few outside this community had seen the self-portraits that these girls shared online to motivate each other. So I felt a moral obligation to confront that problem, to document it in order to draw attention to it.2 In my work On Abortion on the other hand, many of the images are reconstructions. And text is very important as well, both in my research and in the final outcome. I use all the media. I want to create an image of different aspects of a story that is actually invisible. By visualising it, I kind of make it real, I put it in front of you.

SG: So with all these materials you create a new, comprehensive ‘image’ that consists of text and photographs and other sources?

LA: Yes, I’m trying to create visual triggers that make you curious, that make you want to know more. In a way I’m pushing you to look at something you didn’t want to look at. Because I want you to learn and think about a certain subject.

SG: Your publications are often referred to as ‘researched-based photobooks’. Do you think the term applies to your work?

LA: I have always found researching more interesting than producing. But I guess it depends what kind of research we are talking about. On Abortion is a mix of journalistic research, academic research, visual research and a lot of production research – but the result is an artistic product and has a completely different intention or function than, for example, a Ph.D. thesis. I have huge respect for people who do this kind of scientific research, so I struggle with the label. But you know, all these labels change. I’m fine with whatever they call it, as long as it makes sense for what I do – and I guess I read more than I photograph.

SG: Do you have an idea where this “archival impulse” comes from?3 Are images alone no longer trustworthy?

LA: I think we want a better understanding of everything in the world in general. We are more engaged politically, we are more engaged with the planet and with our peers. Images can be very evocative and can stimulate the imagination, but I definitely don’t believe that an image says more than a thousand words. There has always been a romanticised idea of the medium of photography, which I find very dogmatic. I just don’t think that words and images have to compete, that one is better than the other. And this is changing now – people are working in teams, they are collaborating and using different mediums. We are getting more open-minded and that’s a very good thing. So combining texts, images and other materials comes naturally and makes a lot of sense for these kinds of projects.

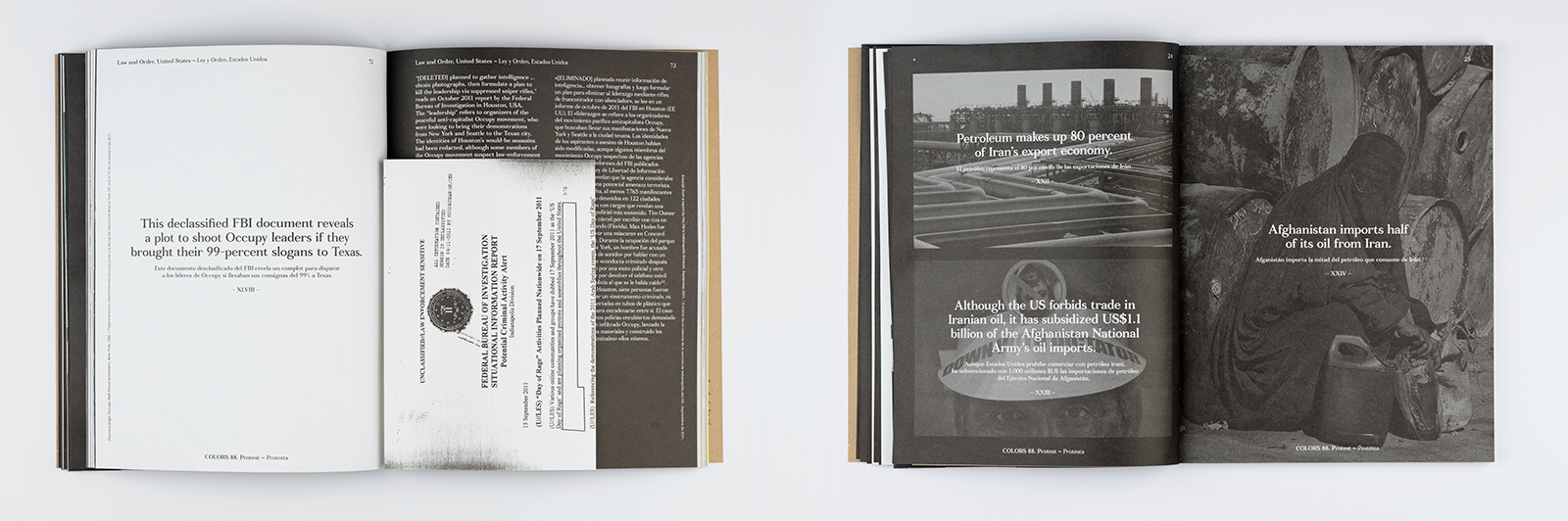

Colors magazines, published by Fabrica, 2012–2013.

SG: Speaking of research: you actually studied journalism before you came to photography. How did this affect the way you approach your material and topics – and to what extent do you use journalistic tools in your work?

LA: For me the key question has always been: What’s important to cover? I never understood why I had to choose between being a writer or a photographer, between following the rules or showing things that mattered to me. I’m not interested in the surface – I want to show what’s underneath and invisible, and that’s very difficult to do with the constrained rules of journalism. When I was working at Colors magazine,4 I learned that I could break or challenge some of those rules and still remain true to the story. The moral compass and ethical code of journalism are very important to me, and always on my mind because my topics are very sensitive. But to be able to use artistic tools in order to tell the story in the best possible way is very liberating and that’s why I prefer to contextualise it as art. Also, writing gave me headaches.

SG: Recently you wrote a short text about Joan Fontcuberta’s5 Fauna, in which you call him a “professional hoaxer”: “The book, based on the fictitious zoologist Dr. Ameisenhaufen’s inventory and fieldstudy work, contains images that appear to be by a successful wildlife photographer, and an incredible amount of ‘research’ supplemented with plenty of documents, sketches, drawings, and X-rays.”6 In a way you are doing the same – using the authority of found documents and artefacts of research as a tool to enhance the authenticity of your story. How do we know we can trust you?

LA: Well, I don’t want to deceive you, I don’t want to lie to you. That’s what Fontcuberta does, but we expect him to do that. You know that this can happen when you’re with him. My intention is to show you things that are real. They are based on facts and I also do fact-checking – but not to prove to you that it is true; I do it for myself to make sure I am not mistaken. I’m not a photojournalist, I don’t reveal my sources; I have a different way of presenting my material. I’m more interested in showing emotions, ideas and concepts that arise and challenge me during my research. I want to explore this and share my perspective with you. And if you’re interested in how I see things, you will trust me.

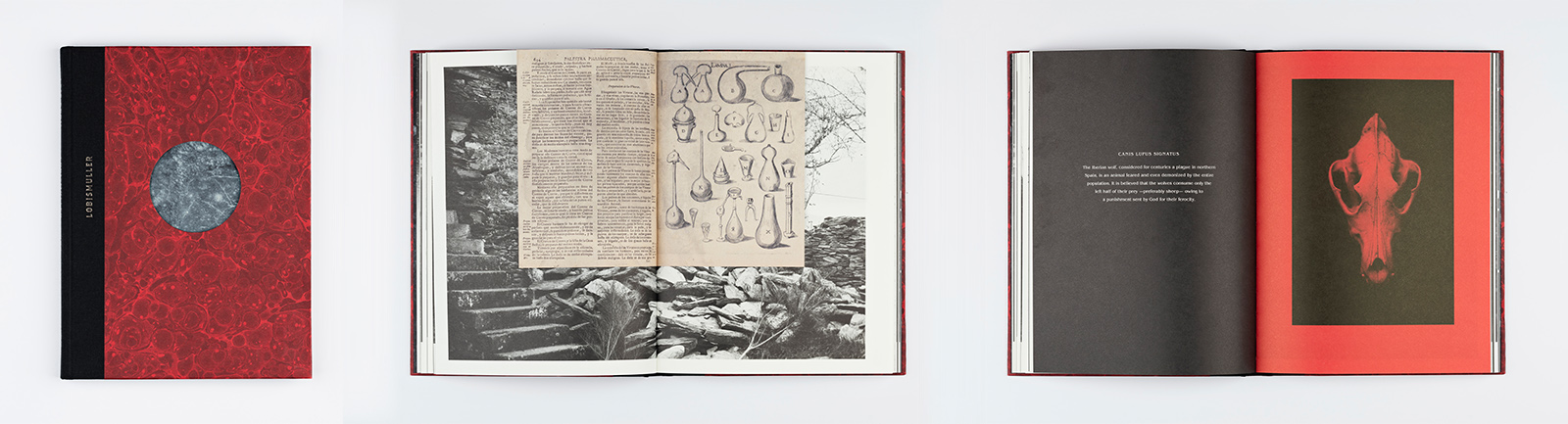

Laia Abril, from the book Lobismuller, Editorial RM/Images Vevey, 2016.

SG: So it’s a question of ethical integrity and being transparent (and therefore authentic and trustworthy) about the way the story is constructed? In your books Lobismuller7 and On Abortion you also included short statements on the copyright page,8 explaining that the projects are based on research but that you also work with interpretations and visual metaphors.

LA: Lobismuller is actually my only project that includes fiction in the storytelling. But it does because fiction was also a reality in this case. The folkloristic tale and mythology that people believed in and shared is a central aspect of the story. The disclosure that I wrote for On Abortion was important for me because it is a very sensitive topic and I didn’t want people to get confused about what they are being shown.

SG: But would you say that anything goes for the sake of the story?

LA: No, certainly not. Every decision has to make sense for the story and everything has to pass a moral or ethical filter. You know, these days we think a lot about representation and privilege and how we show the pain of others, which is a very important conversation. In my work, I might sometimes be on the borderline – and I might even do some things differently in retrospect – but the question of how to represent others has always been a crucial consideration in my work.

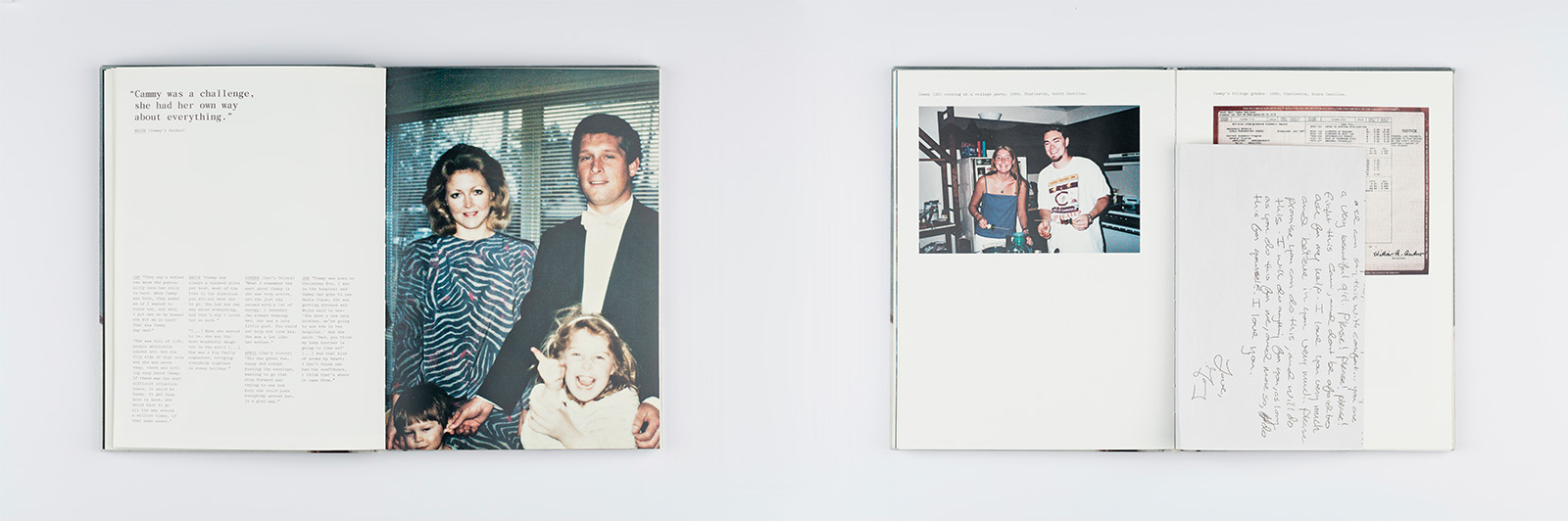

SG: Your handling of images and texts and their special characteristics and functions varies depending on the story you’re telling or the subject you’re focusing on. In The Epilogue9 you reconstruct the absence of Cammy Robinson, who died from the consequences of bulimia when she was 26 years old. The images in the book show the then and now – photos from the family archive and your own portraits of the surviving relatives and friends. The texts consist mainly of quotes from family members and friends, handwritten letters and diary entries, as well as a few explanatory captions for context. You break this illness down to a personal level by giving a voice to the indirect victims and getting your readers attached to Cammy and her social environment. Lobismuller is, as you mentioned before, a fictional reconstruction of the story of Manuel Blanco Romasanta, Spain’s first documented serial killer, who claimed to be a werewolf and, according to new forensic theories, could have lived with a rare syndrome of intersexuality. The main story is told by the text in the captions, while the images consist mainly of land- scapes and function as a stage on which the story unfolds. The images are read and interpreted in relation to the text; they stimulate the imagination and have an immersive, atmospheric function, creating a haunted feeling. In On Abortion your intention was to express feelings while adhering to facts.10 The texts are a combination of rather rational contextualisations and more emotionally charged testimonies by women, while the images range from facsimiles of documents and visual evidence to illustrations or proxy images to condensed symbols and visual metaphors, as well as what you call photo-novels. Has the way you use the images and texts changed and developed over time?

LA: There are definitely similarities and influences between the books because I was working on all three projects more or less in parallel. Combining image and text like a graphic novel in Lobismuller had an influence on the photo-novels in On Abortion, for example. What has changed the most is the amount of text that I use. As my projects became more research-based, I found myself needing more text to elaborate on certain aspects. Also, I’m including more of my own texts. It’s a little bit as if I was shy with text in the beginning and I think the use and meaning of text in my work change in relation to my understanding of where ‘my voice’ is in all of this. The Epilogue was mainly based on interviews and photographs that already existed, so I was working with the voices of others, while my own voice and authorship consisted in the choices I made, the questions I asked and the interview fragments and images I selected for the book, as well as in my own photographs. When I was working on Lobismuller I also had quotes from the killer from the trial but I wasn’t allowed to use them. So this was the first project for which I wrote my own interpretative text – a tale based on other people’s statements. On Abortion is a mix: there’s the personal voice and statements of individuals in the photo- novels, there are factual texts that I wrote myself, and there are the photographs I made, the reconstructions and symbols triggered by the texts. I keep on investigating and understanding my voice. Even if my work focuses mainly on the visuals, we tend to forget how much the accompanying texts influence the interpretation of the images. It’s really important to consider what kind of information you add to the images – and how you express it.

Laia Abril, from the book The Epilogue, Dewi Lewis Publishing, 2014.

SG: So image and text always go hand in hand and influence each other in your projects?

LA: It’s like a conversation between them. Mostly I write the texts and then I create the images, while my viewers will most likely look at the images first and then read the text. That’s an interesting dynamic that also influences the way I write and photograph. For me this temporal interplay between looking and reading is very important because it has an impact on how you access and understand a story.

SG: Let’s take a step back and talk about the genesis and development of your books. After the intensity of researching and collecting, you have to turn this plethora of information into a story. How do you go about editing and creating a narrative?

LA: It’s always challenging to narrow down the material because I gather so many stories and aspects that I want to tell. I don’t want to miss a community, a different background … but of course you can’t represent everybody. So I’m trying to find a ‘conceptual umbrella’, like in On Abortion, by focusing on the repercussions of lack of access to abortion. I’m also thinking about my audience and the kind of experience they will have. How it will feel to turn the pages, how long you can stay with a topic, when do you get bored, how much you can bear. I’m not only searching for a visual rhythm but also for an emotional rhythm. I’m trying to make it interesting.

SG: In recent years you have been working in a creative partnership with the designer Ramon Pez – on your own books, but also on the design and editing of Cristina de Middel’s self-published book The Afronauts (2012) and other projects. Can you describe your collaboration?

LA: Ramon and I met at Colors magazine many years ago.11 We started working on Cristina’s book and eventually on my books. Together we evolved the methodology we learned at Colors and applied it to book-making. Actually, most of the people I work with are from Fabrica, from Colors. Ramon and I have been doing this for a long time, but since On Abortion the collaboration has become less intense since my own design skills have improved. The work had already been shown in an exhibition and designed for the wall, so I had a clearer idea of how to translate it into a book. Also, as I gain experience, I’ve been carrying out more of these tasks on my own, while delegating others that I’m not so comfortable with. But in terms of design I owe everything that I learned to Ramon and the Colors art directors.

SG: It’s interesting to see how the methodology of a magazine translates into the context of a book, and there are actually quite a few parallels between Colors and your publications. Designwise – the changes of paper format and materiality, the fold-outs and various layers of information – but also in the way in which stories, causes and consequences are researched worldwide, how different perspectives are brought together in a kind of ‘visual investigation’. Could you elaborate a little bit on the influences of this methodology?

LA: One important thing that I learned from Colors was the interplay and equal importance of image, text, design and production. The way of working was very democratic and networked: designers were also researching the story and researchers gave input for the design. All the components were equally significant and we had lots of ‘ping-pong conversations’ to make sure that there was a reason behind every decision: Why should this be in colour? Why does this have to be shiny? Does this help to get attention? Does this make an aspect stronger? When making a book, these considerations are equally important because a photobook is much more than a collection of photographs.

Pages from Colors magazine #88, Protest – A Survival Guide, Fabrica, 2013.

SG: So the various decisions led to what Ramon Pez calls a “multidimensional architecture”? He recently said in an interview: “I consider the layout like a musical pentagram, where the layers, compositions, spatial relations, proportions, and emptiness structure the rhythm of the reading, and the perception of the story. The relationship between text and images will answer to the chances made by this multidimensional architecture. And let’s keep in mind that text also has a visual narrative potential.”12

LA: Yes, and for me it’s not only the design and the visual narrative but also the aforementioned emotional rhythm that makes a difference. You could also compare it to a culinary recipe: you have various pieces of information, you add layers and emotions, and you always have to find a balance between all the ingredients, so it doesn’t get too salty, too spicy or too intense. And for every subject you need to find an individual recipe; the content and context have an impact on the form.

SG: The different layers of information and contextualisation, the multiple narrative threads and interruptions through pull-outs and inserts in your books also remind me of the multilayered, fragmented and interactive way we nowadays receive, consume and process information through the Internet. How important is the Internet for your pro- cess and has it influenced the conception of your photobooks?

LA: Absolutely. I’m a millennial and a child of the Internet generation. I spend hours researching online and always find it fascinating. Of course I also read and research on paper but with the Internet, information has just become so much easier to access. I find most of my stories and characters online and would not be able to do what I do without the Internet. In recent years there have been theories that online storytelling is moving from the classical hypertext and link structure to one-pagers that you just scroll through. This actually worries me a little bit because scrolling makes you rather numb, while to follow links you have to be more active and seek connections yourself.13 This is definitely the kind of information processing that I’m aiming to implement in my books.

SG: You also divide your work into chapters that are part of overarching long-term projects like On Eating Disorders and A History of Misogyny. What are the advantages of this method of working?

LA: The chapters allow me to focus on different aspects or subtopics and to choose different settings, aesthetics and perspectives for them. They also help to organise and structure these vast topics. I guess I’m also a product of the first wave of television series, like Lost.14 The way we perceive information nowadays is often divided into episodes and seasons, and I think that influenced me as well.

SG: One of those chapters was On Abortion, which was published as a book and met with critical acclaim. Yet the work was initially conceived as an exhibition and shown in 2016 at the photo festival ‘Rencontres de la Photographie’ in Arles, and later elsewhere. What were the challenges of recontextualising the story? Where do you see the possibilities and limits in both contexts regarding the narrative and the relationship between image and text?

LA: It was a big challenge to translate the physical experience of walking through an exhibition into a book. When I first started conceptualising, I put object after object just as if it was designed for the wall, but it looked like a catalogue. There was no narrative like in my previous books. Eventually the text was the key to reorganising everything and creating a different kind of narrative. That’s one big advantage of the book – you can add more text or longer interviews that no one would read in a show. So I’m trying to create a different experience, depending on the platform and audience. In a way it’s also nice to do the exhibition first, to see how people react, digest that and then continue with the book. Because the book lasts forever and it’s a huge responsibility.

SG: You mentioned your audience – what’s your relationship to your readers and viewers and what feedback do you get about your work?

LA: I demand a lot from my audience. They need to spend money, invest time, read a lot, digest, and commit to a subject that might not have interested them in the beginning. But in exchange I’m also trying to give them the best I can. I let them walk into my mind and share my views on a subject that I have investigated, visualised, transformed and filtered for them. The feedback I receive is mainly positive and very touching at times. It means a lot to me and I’m very grateful for it.

SG: In January you exhibited chapter two of A History of Misogyny: On Rape – for which you received the Tim Hetherington Trust Visionary Award (2018) and the Magnum Foundation Grant (2019) – at Galerie Les Filles du Calvaire in Paris. What’s your focus in this chapter and how will it differ from the previous ones?

LA: The project aims to call out the institutional rape culture that is prevalent in societies around the world. I’m looking at rape by exploring how concepts of power, law and cultural belief relate to the constructions of the notion of masculinity and sexual violence. For a long time, people have been surrounded with stories, images, language and other everyday inputs that validate the objectification of the female body as a property. The chapter will follow the concept and style of On Abortion but will offer a much more personal perspective. It’s like a visual essay on my reactions to different pieces of information that exemplify the injustice inherent to rape power dynamics.

This conversation took place via phone, 27 September 2019.

Erschienen in: Karen Fromm, Sophia Greiff, Malte Radtki und Anna Stemmler (Hg.): image/con/text. Dokumentarische Praktiken zwischen Journalismus, Kunst und Aktivismus, Berlin 2020, S. 150-161.

| 1 | Abril’s first long-term work On Eating Disorders comprises the multimedia project A Bad Day (2010) about the daily struggles of a girl with bulimia, the self-published zine Thinspiration (2012) focusing on the pro-anorexic community, and the book The Epilogue (Stockport 2014) about a family that lost their daughter to bulimia. Her second long-term project, A History of Misogyny, is an ongoing visual archive of the systemic control of women’s bodies across time and cultures. Chapter one, On Abortion. And the Repercussions of Lack of Access (Stockport 2018), highlights the consequences of lack of access to abortion, while chapter two, On Rape (solo show at Galerie Les Filles du Calvaire, Paris, 25 January to 22 February 2020), focuses on institutionalised injustice and institutional rape culture. |

| 2 | Laia Abril is referring to her project Thinspiration, self-published zine, 2012, designed in collaboration with art director Ramon Pez and Guillermo Brotons. |

| 3 | The reference is to Hal Foster, “An Archival Impulse”, in: October 110 (autumn 2004), pp. 3–22. |

| 4 | In 2009 Laia Abril enrolled in a five-year artist’s residency at Fabrica, the Benetton Communication Research Centre in Treviso, Italy, where she worked as a researcher, photo editor and staff photographer at Colors magazine. The magazine was founded in 1991 by photographer Oliviero Toscani and art director Tibor Kalman. It is published quarterly, with each issue focusing on a single topic and following it around the world. |

| 5 | See also Joan Fontcuberta’s contribution in this volume. |

| 6 | Laia Abril, “Fauna. Laia Abril on Joan Fontcuberta and Pere Formiguera”, in: The PhotoBook Review 16, spring 2019, p. 18. |

| 7 | While mainly creating works that are based on verifiable facts and remain close to reality, with her book Lobismuller (Barcelona/Mexico 2016) Laia Abril has created a multilayered, semi-fictional narration, employing superstition and hearsay to relate real events. |

| 8 | On Abortion: “This project is a visual analysis and interpretation by the artist of the repercussions of lack of access to abortion in the world. Some of the images in this book are reconstructions or visual metaphors based on information discovered through extensive research.” Lobismueller: “The texts in this book are based on transcripts of the trial of Manuel Blanco Romasanta, on the research, reports, and studies of Félix and Cástor Castro, Fernando Serrulla, and Marga Sanín, among many others, and on accounts and rumors circulating among local residents and the folklore surrounding them, including the research and/or dramatizations created by the media and the author’s own journalistic and artistic interpretation.” |

| 9 | See also Anja Schürmann’s contribution in this volume. |

| 10 | See Laia Abril, On Abortion. And the Repercussions of Lack of Access, in this volume. |

| 11 | Ramon Pez worked as Art Director at Colors magazine from January 2008 to July 2009 and from January 2012 to December 2014. |

| 12 | Matthieu Nicol, “Design as Choreography. Compiled by Matthieu Nicol. Including contributions by Ania Nałęcka, Ramon Pez, Izet Sheshivari, and Elana Schlenker”, in: The PhotoBook Review 16, spring 2019, pp. 6 f. |

| 13 | See also Fred Ritchin’s contribution in this volume.. |

| 14 | The American television series Lost originally aired on ABC between 2004 and 2010. |

English

English